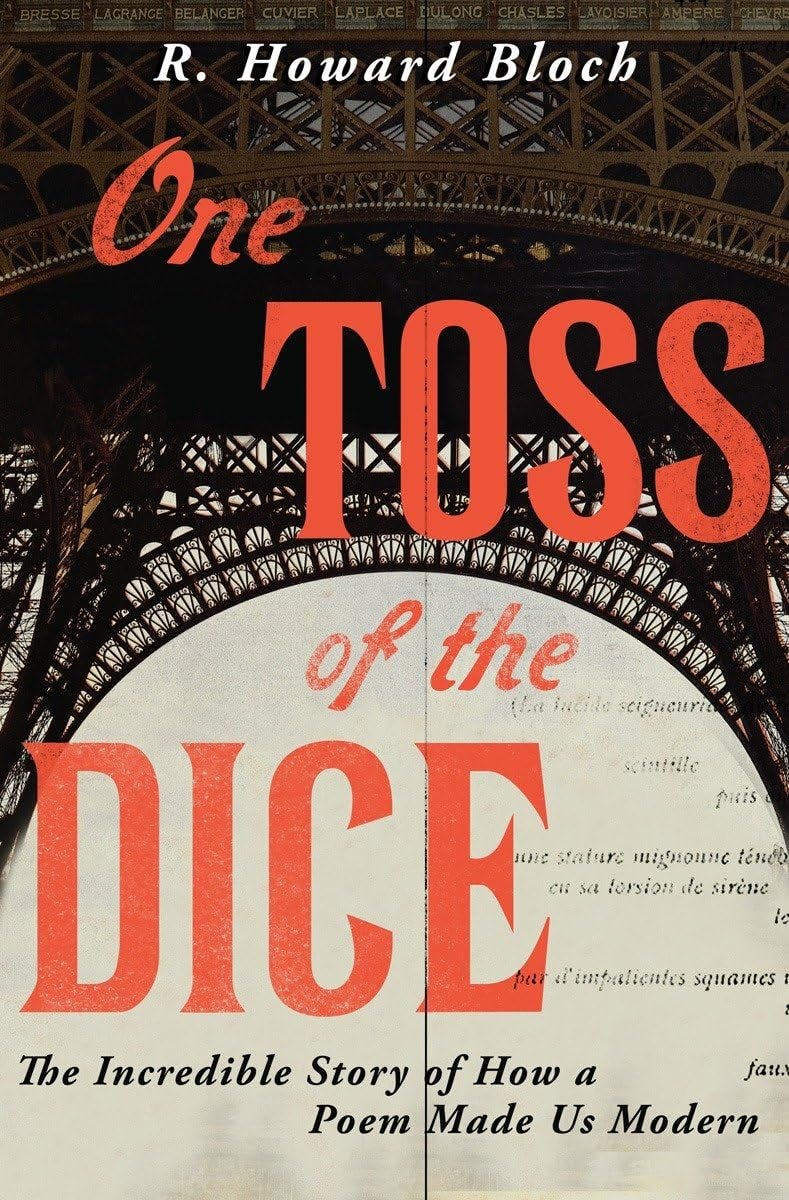

One Toss of the Dice: The Incredible Story of How a Poem Made Us Modern

R. Howard Bloch

320 pg., Liverlight, 2016

I just finished One Toss of the Dice, about Stéphan Mallarmé and the winding journey of his life and career, which culminated in the penning of an arguably revolutionary poem. “One Toss of the Dice” (“Un Coup de Dés”) has long been considered an epoch-changing, and a work I’ve long wanted to learn more about. Still, the subtitle in my view (“The Incredible Story of How a Poem Made Us Modern”) promises too much. Is it an “incredible” story? Sorta. Did the poem “make us modern”? It was experimental and foresightful, sure; it expressed the cultural moment, yes. And there were interesting near-contemporaneous circumstances and analogous breakthrough artworks and ideas, some of striking coincidence, in fields as wide-ranging and varied as anthropology, astrophysics, and music. But much the same could be argued for a number of modernist works, and in the end I felt unconvinced that this work in particular holds pride of place over against the cumulative effect of many good (but few truly great) poets that make up the pivotal shift we know as Modernism.

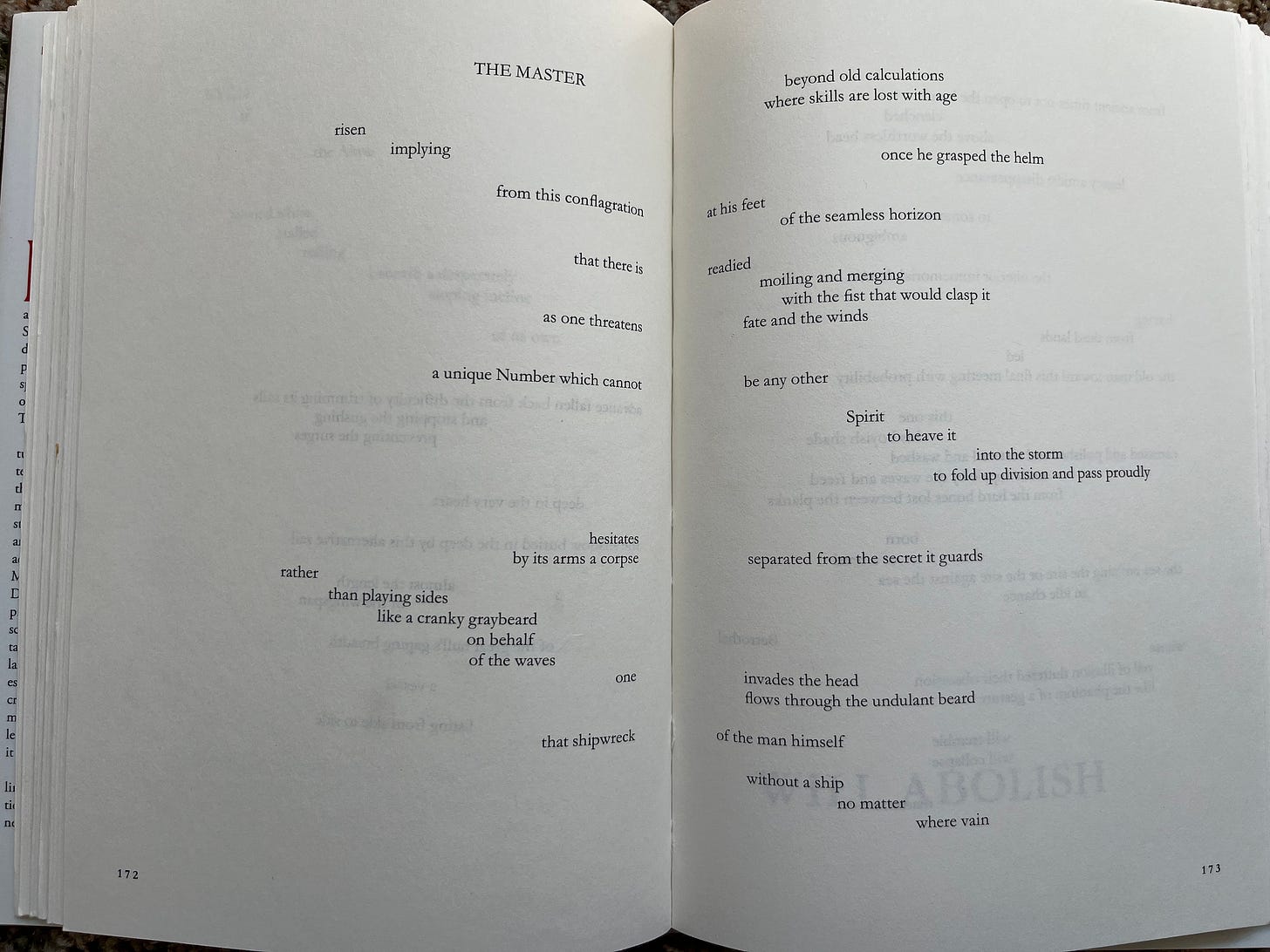

Still, it’s a good concept for a book. At the center is the original French text and an English translation (by McClatchy), each version taking up the luxurious full spread real estate Mallarmé intended (see photo below). On either side is Bloch’s biographic historyt: five chapters before the poem trace Mallarmé’s birth to the poem’s publication, and three chapters after the poem focus on reception history and cultural significance. The first half of the book is strong, as Mallarmé’s life is rich material. In fact, one soon catches on that “Un Coup de Dés” is important just as much for being the magnum opus of a literary icon as for being an inherently worthy work. Even so, Mallarmé’s greatness is possible more theoretical than actual. His entire career pitched toward a “great work,” “The Book,” which was never written, barely started, so his greatness must be established on a small handful of works and unpublished notes. Bloch’s biographical sketch makes clear Mallarmé’s importance lies in the fact that was a teacher of poets and at the center of Paris’s literary circle at a defining moment. This makes a strong case for the enshrinement of “Un Coup,” even if, in the end, the poet seems more important than the poem.

The poem itself remains difficult and abstract. Bloch shows us what it tries to do is, but as someone who first approached modern poetry from the Anglophone point of view, I found “Un Coup” a lesser version of ambitious modernist works that, while they owe something to Mallarmé, are more fun and interesting. The poem can be credited with inventing concrete poetry and (possibly) free verse, but prototypes are not often the full instantiation of the vision. That’s possibly unfair to Mallarmé, but even Bloch admits the syntax and diction of the poem are all but incomprehensible, thus our appreciate is limited, mostly, to the conceptual type.

Nevertheless, the book a good example of a hybrid genre (literal biography, cultural history, and criticism) meant for a popular audience. And, despite the target readership, Bloch does not shy away from stylistic and linguistic nitty-gritty, which I appreciate. His historical-aesthetic approach yields a real sense of the work’s importance in culture, art, and philosophy. And in addition to occupying a part of the story of the modern poem, the book deepens one’s feel for the art world of late 19th century Paris (and as someone off-and-on-again working my way through Proust, I liked this secondary benefit.)

Recommend for connoisseurs of French cultural history and those interested broadly in modernism and the history of ideas, but not necessarily for those looking for a mind-blowing new poem or poet.